100 million years ago, a group of bark beetles started to farm their fungal symbionts and formed a tight relationship with the fungal crops. Such lifeform between bark beetles and their fungi is termed ambrosia symbiosis, and therefore “ambrosia” beetles and “ambrosia” fungi for these critters involved.

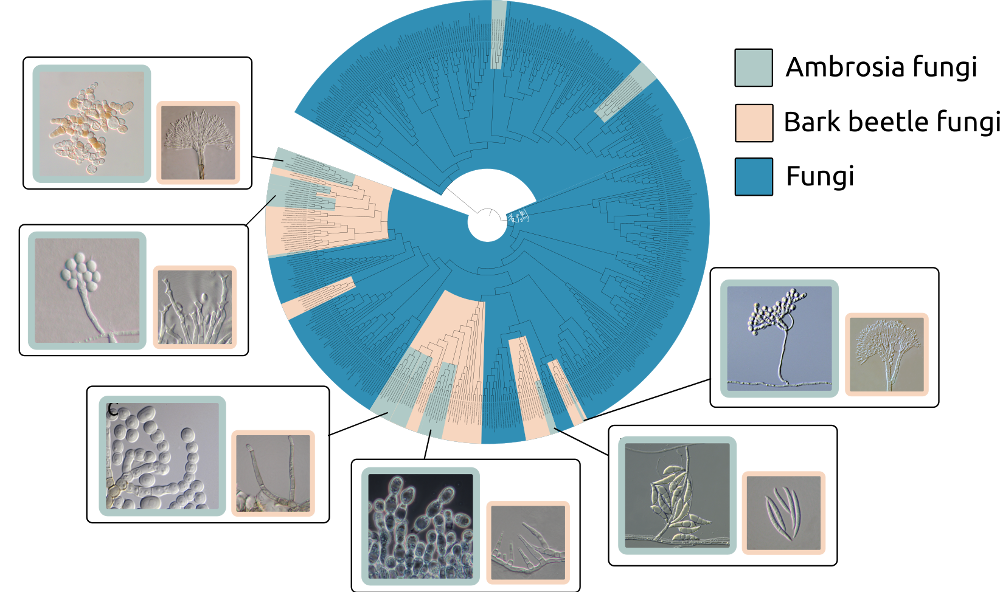

Diverse origins and enlarged ambrosia cells of ambrosia fungi.

The ambrosia lifeform is currently the earliest known agriculture in insects, and perhaps in animals. The farmer beetles are fully reliant on the farmed fungi for food sources, in return, the beetles are the only vehicle for the fungi, which, otherwise, be left in the doomed environment. Therefore, ambrosia beetles and ambrosia fungi are in mutualistic, obligate relationships.

Based on the evolutionary trees, there are at least 12–16 times of bark beetles turning to the ambrosia lifestyle. Likewise, more than 13 times of fungal lineages are adapted to be ambrosia crops.

Surprisingly (or perhaps unsurprisingly), the ambrosia lifestyle fixes the involved beetles and fungi in such a form and never turns back to their original independent lifestyle (free-living). So, what fixes them in the relationship? Does it achieve physically, chemically, metabolically, or others? Can we detect it in their genomic, metabolic, or phenotypic features?

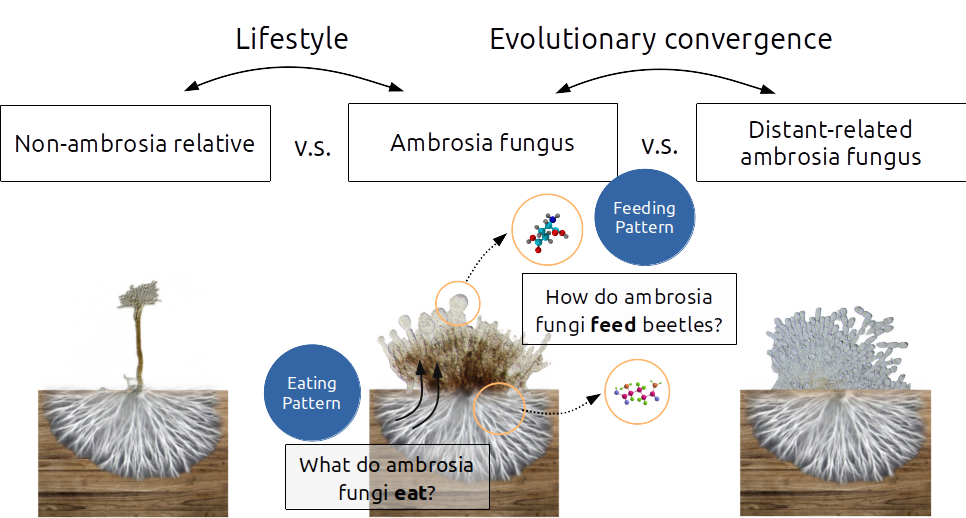

To answer the questions, we designed an experiment to examine the eating and feeding pattern of ambrosia fungi. We profiled the eating pattern of fungi using the Biolog microarray system for their usage of 190 different carbohydrates, and profiled the feeding pattern using the Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) for all metabolites present in their cells.

We strategically selected six phylogenetically unrelated pairs of fungi including an ambrosia and a non-ambroisa in each pair. The design allowed us to comparatively study the evolutionary trajectory of unrelated ambrosia fungi to understand how they all land on the ambrosia lifestyle.

Comparative study of the eating and feeding patterns of ambrosia fungi.

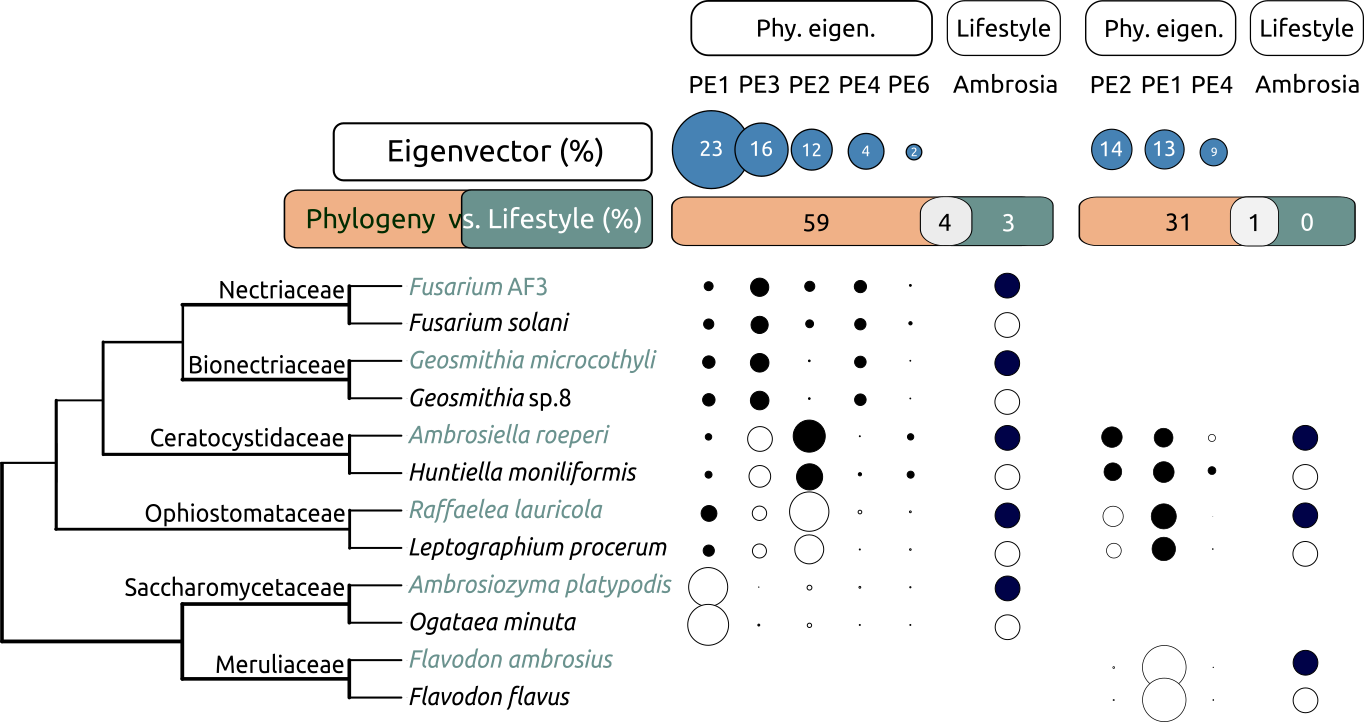

The result revealed that these fungi became ambrosial in different ways, and likely influenced a lot by their phylogenetic background. We found phylogeny alone can explain 59% and 31% of the variations in their eating and feeding patterns. There were almost nothing of the variations explained by the ambrosia lifestyle. It suggested that ambrosia fungi keep much of the metabolic capacity as their non-ambrosial ancestors when adapted to be the crops.

Phylogeny matters when talking about the metabolic patterns of ambrosia fungi. [adapted from Huang et al. (2019 & 2020)]

The result does highlight the great divergence of ecological niches and phylogenetic origins of ambrosia fungi. A conserved metabolism inherited from their ancestors which might have been optimized for distinct niches would be a rational and safe strategy for fungi. In fact, the functional redundancy has been shown in many associated fungi in ambrosia symbiosis. It indicates that the nutritional-oriented evolution of fungi to feed the vector beetles may not be that strongly enforced in the ambrosia system.

Reference cited

- Huang Y-T, Skelton J, Hulcr J. Lipids and small metabolites provisioned by ambrosia fungi to symbiotic beetles are phylogeny-dependent, not convergent. ISME J. 2020; 14: 1089–1099.

- Huang Y-T, Skelton J, Hulcr J. Multiple evolutionary origins lead to diversity in the metabolic profiles of ambrosia fungi. Fungal Ecol 2019; 38: 80–88.